by Dennis Dalman

news@thenewsleaders.com

After her 14-year-old son, Taylor, committed suicide, the grieving process is never-ending for Kristine Brugh of Sartell, who keeps asking herself questions that have no answers.

“Why didn’t I tell him I love him the last time I saw him?”

“Were his problems diagnosed incorrectly?”

“How could such a sweet boy turn into somebody I didn’t know?”

“Why do so many people, including schools, want to avoid the topic of teen suicide?”

Taylor’s taking of his own life remains a heartbreaking mystery to his mother. The unthinkable tragedy happened May 14, 2013 when Taylor shot himself in a basement area of his father’s house in St. Cloud. Kristine and Taylor’s father had been divorced years ago. Taylor and his brother, Tanner, then 12, shared a bedroom at their father’s house when they would visit him. It was Tanner who found Taylor dead. He frantically called his mother.

At first, Kristine thought Tanner was yelling something about how Taylor had “cut” himself since he had been known to do “cutting” before – making cuts or scratches on his skin, a compulsive behavior that afflicts some young people.

Then Kristine, in another split second, heard the word “dead,” and in that split second her world reeled crazily, crashing down in devastation, and then her heart broke.

What was so horrible and baffling for Kristine is that just two days before, on Mother’s Day, Taylor was his loving sweet old self again, and he and his mother had the most pleasant time, going to church, talking, laughing.

But then the very day after Mother’s Day, Taylor plunged into a dark side again. She found out he’d left school early with some of the “rough” kids he’d been hanging around with. He wouldn’t answer his cell phone.

“I begged a police officer to find him and arrest him,” she recalled. “I didn’t know what else to do. But the officer couldn’t arrest him.”

Finally, Kristine drove around to places she thought Taylor might be. Crying, she drove here, there and everywhere until, finally, she found him sitting on a bench with friends at Sartell’s Watab Park.

“Get in the car!” she told him, angrily.

She decided to drive him to his father’s house in St. Cloud. Utterly frazzled, she did not know what else to do or how to handle him.

“I’m tired of your lies,” she said. “You’re always lying to me. Your dad can deal with you.”

Taylor, crying, said, “I just want to kill myself.”

The threat sent a wave of dread through his mother. When they reached the father’s house, Kristine – out of ear shot of Taylor – cautioned those there to keep a very close eye on Taylor all through the night as he had threatened to harm himself.

Just hours later, doom struck.

“I felt so guilty,” his mother said. “I didn’t tell him ‘I love you!’ “

Early years

Taylor and Tanner spent their early years with their parents in St. Cloud.

Kristine began to notice, when Taylor was only 4 years old, that he sometimes had a hard time dealing with things. He would throw tantrums and collapse into virtual meltdowns. She would have to hold him tight during those times for fear he might fling himself into something and hurt himself.

About that time, Kristine obtained a divorce. She took Taylor to counseling, and it seemed to help.

“Then everything seemed fine,” she recalled. “He was polite, friendly, a leader in school. He was outgoing and had lots of friends.”

About three years ago, Kristine and the two boys moved to Sartell.

“Taylor hated that we moved,” she said. “He still made contact with his friends from the St. Cloud school, Westwood.”

In Sartell, Taylor began to come undone. He fit in at first in school, and teachers and fellow students liked him very much. But in the afternoons, after school, he would come home moody.

“He loved music and even wrote his own rap songs, but some were devastating to read because they were about people not liking him and how he didn’t fit in” Kristine recalled. “He was so good at hiding his real feelings, even right before the day he died. He played football in school, but later his grades went down, although he didn’t seem depressed. He’d never been in trouble before – ever – until eighth grade.”

At the time, Kristine was hoping it was the sudden onset of puberty that was causing Taylor’s unpredictable behavior.

It was around Christmas time in 2012 that Taylor spiraled out of control. He began an infatuation with a girlfriend from his former school, and problems worsened: verbal scuffles with school officials, church members, counselors and now and then skipping school.

“The last year of his life was hell,” she said. “I knew he was such a sweet boy, but he’d turned into somebody I didn’t know.”

Teeter-Totter

Throughout the last year of Taylor’s life, he and his mother went through a teeter-totter of emotions. At one point, all seemed fine, and they would both be feeling up and having a happy time with good communication between them, and then – suddenly, with no warning – moods would plummet downward, and Taylor again would turn into a frightening young stranger to his mother.

In the best of times, Kristine and her sons would choose a state on a United States map, agree on a destination and then take a 10-day trip to that state. They always had a ball traveling together.

But such good times could so easily give way to bad times during the last year of Taylor’s life. School officials would often call Kristine, often during her lunch time at work, because of some problem with Taylor. She always broke off what she was doing and went to school to see what the matter was.

One night, during an April snowstorm, Kristine woke up and just knew by a mother’s instinct something was wrong.

Taylor’s bedroom door was locked from the inside, but Kristine just knew he was not in the room.

She called the police. After worry, pacing and agony, Taylor returned the next morning.

Just three weeks before he died, Taylor chose to go to church with his mother.

“He’s making good choices,” she thought to herself. “He’s turning around.”

One day in April, he skipped school, and they called the police. His mother wondered if he was doing some kind of illicit drugs, but there was no proof of that.

Meantime, Taylor was being treated for depression and anxiety after being diagnosed with possibly a borderline personality disorder.

In his writings, Taylor often noted he felt his mother and his brother did not love him and he was always disappointing them, not living up to their expectations. His attitude was baffling because she and Tanner always loved and supported him, thick and thin.

“We had a great relationship,” Kristine recalled.

Analysis

Kristine has spent many agonizing hours pondering what went wrong, what could have been changed, how could the suicide have been prevented?

“I was doing everything I could do (to help him),” she said.

Her children did not like the fact their mother worked so hard. She had always worked for herself, for years as a hair stylist and for a time as general manager of her boyfriend’s restaurant. For years, Kristine and Taylor shared a happy secret – that someday, soon as possible, she would open her own business. It gave them both something to look forward to in times of trouble.

After Taylor’s death, Kristine spoke with many of his friends. She also talked at her church, The Waters Church. She is determined to reach out to help prevent suicides, but her efforts are sometimes stymied. She wanted to talk to Tanner’s class in school, but school officials nixed the idea, fearing that talk about suicide might cause, through a spin-off effect, one or another student attempting such a drastic act.

Kristine also wants to start a suicide-prevention support group and a group for loved ones of suicide victims.

“I don’t know the answer,” said Kristine, who is left with only a series of “maybes” to every question she’s asked.

But some things she does know, one of which society cannot brush off the topic of teen suicide.

“We cannot ignore the subject,” she said. “We can’t hush this stuff up. The problem’s getting worse and worse, and I feel we’re not doing anything about it. We’re not doing enough.”

Parents, she said, should never minimize children’s problems and not dismiss them by blithely saying, “Oh, just get over it!”

When kids are hurting, such as when they are jilted after a love crush, they should be taken very seriously, Kristine believes.

“To a kid, a crush is everything,” she said. “The girl Taylor knew was a lifeline, and both of them were dealing with issues.”

It makes Kristine angry when she hears people say that suicide is a selfish act.

“It wasn’t selfish!” she said. “I just know what he must have felt like. He felt there was no other way out of those feelings than to do what he did. He didn’t have the capacity to think at the time because he was feeling so down. He was hurting so bad he just wanted it to stop.”

Sensitive professionals can be a big help during crises, Kristine said. Police officer Dan Whitson and a school counselor treated Taylor with the utmost respect even when he had serious troubles in school. They also went to bat for Kristine when she requested to speak in the school. Having that kind of support from professionals, she said, gave her strength and courage to go on.

Always take suicide threats seriously and intervene, Kristine advises.

“If a kid in school says something like, ‘My life sucks; I just wanna die,’ that is a call for help,” she said. “Report it and get help immediately for that person from school officials, parents or someone else.”

Secret come true

The sweet secret Kristine and Taylor shared years ago has come true: Kristine recently opened her business, Spa Nala, in Sartell. She does laser treatments for hair removal, tattoo removal, skin rejuvenation and the erasure of sun spots and scars. She’s recently added Botox treatments and massage therapy.

Sadly, Taylor is not here to realize their secret-come-true.

Kristine’s Spa Nala logo is a circle of life, designed with Taylor and Tanner in mind.

“Tanner and I are still evolving, helping each other as we learn to live with only Taylor’s memory now.”

How Spa Nala got it’s name

In late 2012, while Taylor Brugh was battling depression and his family was trying to help him, his mother Kristine had a dream about opening a laser spa. She and her two boys, Taylor and Tanner, were looking for a way to have Kristine spend more time with her sons. Right after she had that dream, an unusual circumstance happened.

“It was late October,” Kristine said. “I remember there was snow on the ground and it was cold outside. One night I saw a small animal in the distance. Upon approaching it I discovered it was a very small kitten. I scooped her up and brought her into the house. She couldn’t have been more than a few weeks old. She was starving and cold and I’m sure she would not have made it through the night. I convinced myself I was only going to nurse her back to health and then I would find her a good home. Little did I know the home I would find for her was mine. She was the sweetest kitten I had ever known, and since I already had a Simba and Pumba at home, it was only fitting to name her Nala.”

After Taylor’s tragic death in spring 2013, Kristine had to fight to move on with her life. Her second son Tanner needed her.

“Then Taylor spoke to me,” Kristine said. “He said, ‘Mom you have to go on for Tanner and me. We created this dream and now you must complete it. You can do this mom. Tanner needs you too.’ So once again, I put all my faith and trust in God who has kept all his promises thus far. I pushed forward creating a spa in honor of Taylor.”

Kristine says she thanks God for Tanner and for the 14 years she was able to have with Taylor. She also counts her blessings and says “God’s protection has surrounded Tanner and me during this past year – including many, many friends and family.”

“I couldn’t have done it without all of your support,” she continued. “Thank you everyone for supporting me while I fought to carry out Taylor’s wishes, all the while preserving his memory and presence thru Spa Nala.”

And the spa’s name is more than fitting, especially since “Nala” in African culture means “successful and beloved.”

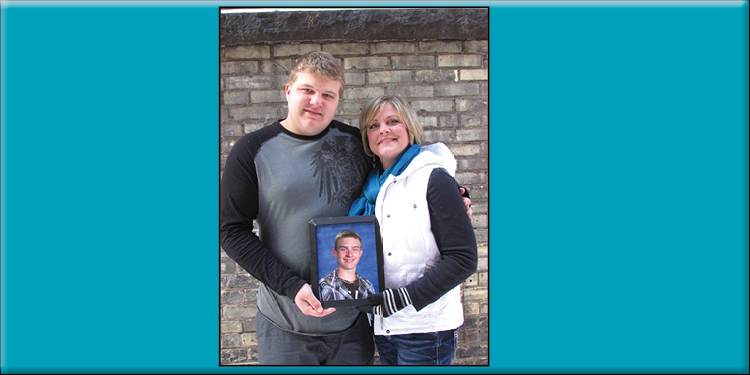

contributed photo

Tanner and Kristine Brugh hold a photo of their loved one – Taylor, the son and brother who committed suicide when he was only 14. Kristine and Tanner, who find strength in each other, continue to mourn Taylor’s tragic loss.