by Dennis Dalman

When it comes to three generations of Joseph John O’Connells (that’s right – I, II, III), it can truly be said, “They just don’t make ‘em like that anymore.”

Julianne O’Connell, a retired teacher and librarian who grew up in Collegeville and still lives there, recalled her colorful paternal lineage.

When O’Connell’s mother, Jody, died at age 90, memories came rushing from the past as if over a long-distance telephone line. At the Collegeville home where Julianne lived with her mother and a brother, the mother, Jody, died at home at age 90 this past summer. The brother had no more need for a land-line phone so Julianne had the phone service disconnected – the AT&T phone service they’d had since 1955.

That disconnection day, ironically, sparked a renewed connection to O’Connell’s heritage.

Her great-great grandfather, Chicago-born Joseph John O’Connell I, had been a self-taught inventor, a born genius, one of the early pioneers of the telephone industry. Among his many innovations was the party-line system, which for decades made it possible, unwittingly, for some telephone users to slyly “listen in” to the conversations of others. At one time, “party line” became a virtual synonym for “snoopy gossip.” That “listen in” capability was used as a basis for a plot device or comic gag in many songs, TV sit-coms and movies of yore, such as the 1959 romantic comedy “Pillow Talk,” a smash hit starring Doris Day and Rock Hudson.

The actual reason for the party line, starting in 1878 with the first switchboard system, was a way to share fewer telephone lines among multiple users, especially in sparsely populated rural areas served by one or two lines over many miles. O’Connell’s invention made it possible to share more than one conversation on a single telephone line.

Among O’Connell’s other inventions were many innovations for telephone-exchange apparatuses, electric circuits and switchboard functions, introducing the pay telephone to Japan, coin collectors for telephone toll lines, the coin-return function and many more ingenious adaptations and improvements.

Julianne O’Connell, born in 1965, never met her esteemed great-great grandfather. Born in 1861, he died at age 98 in 1959 after working for the Chicago Telephone Company for more than 50 years. His life-long Chicago home is now a historic landmark.

Though she never met him, Julianne O’Connell was well aware of the memories of him shared by relatives.

“He could remember that when he was a child he saw the train carrying Abraham Lincoln’s body back to Illinois for his burial (in Springfield),” she said. “He was a precocious kid, never went to college, a self-taught engineer.”

And he was a wild card and a bit of a daredevil, always trying something naughty or new.

“He played with dynamite and used to blow up outhouses,” she said. “He even anticipated jet propulsion by hooking up a single-barrel shotgun to a boat, with the barrel in the water, then pulling the trigger. He tried everything, and he could do anything. He had the most fascinating life.”

Joseph John O’Connell II, Julianne’s grandfather, was a craftsman and vocational-school headmaster. He and his wife, Margaret, lived right next door to his father’s house.

Like his father, O’Connell II also was a bit of a flamboyant wild card.

“He had a cannon in his yard, and on the Fourth of July he’d blow that thing off,” she said.

Julianne’s father, Joseph John O’Connell III, was born in 1927 in Chicago. Multi-talented, never afraid to try anything new, he was by turns an apprentice typesetter, a cab driver, an office worker and jazz saxophonist.

He enlisted during World War II in the U.S. Air Corps and participated in many actions in the war, including in the South Pacific.

Back in Chicago, he took up schooling, including at the American Academy of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. Later, he moved to Collegeville and set up home, eventually having three sons and two daughters. He had purchased that property by selling some of his stocks in the American Telephone and Telegraph Co., of which his grandfather was such a distinguished pioneer.

At St. John’s University and the College of St. Benedict, O’Connell was an art teacher, artist-in-residence and mentor. He was a printmaker, painter and – most famously – a widely admired sculptor and many of his works still adorn the interiors of the buildings at CSB and SJU. O’Connell III died at home of cancer in 1995 at the age of 68. News of his death brought widespread tributes from colleagues and admirers far and wide.

Why did her great-great grandfather, the grandfather and the father all share the same name, Joseph John O’Connell?

“I really don’t know,” said Julianne. “They were all very Irish. It might have had something to do with that Irish pride – keeping the same name in each generation.”

Julianne recalls getting the last land-line phone bill before she dropped the service last summer.

“And there was dad’s name,” she said. “Still on the bill after all those years.”

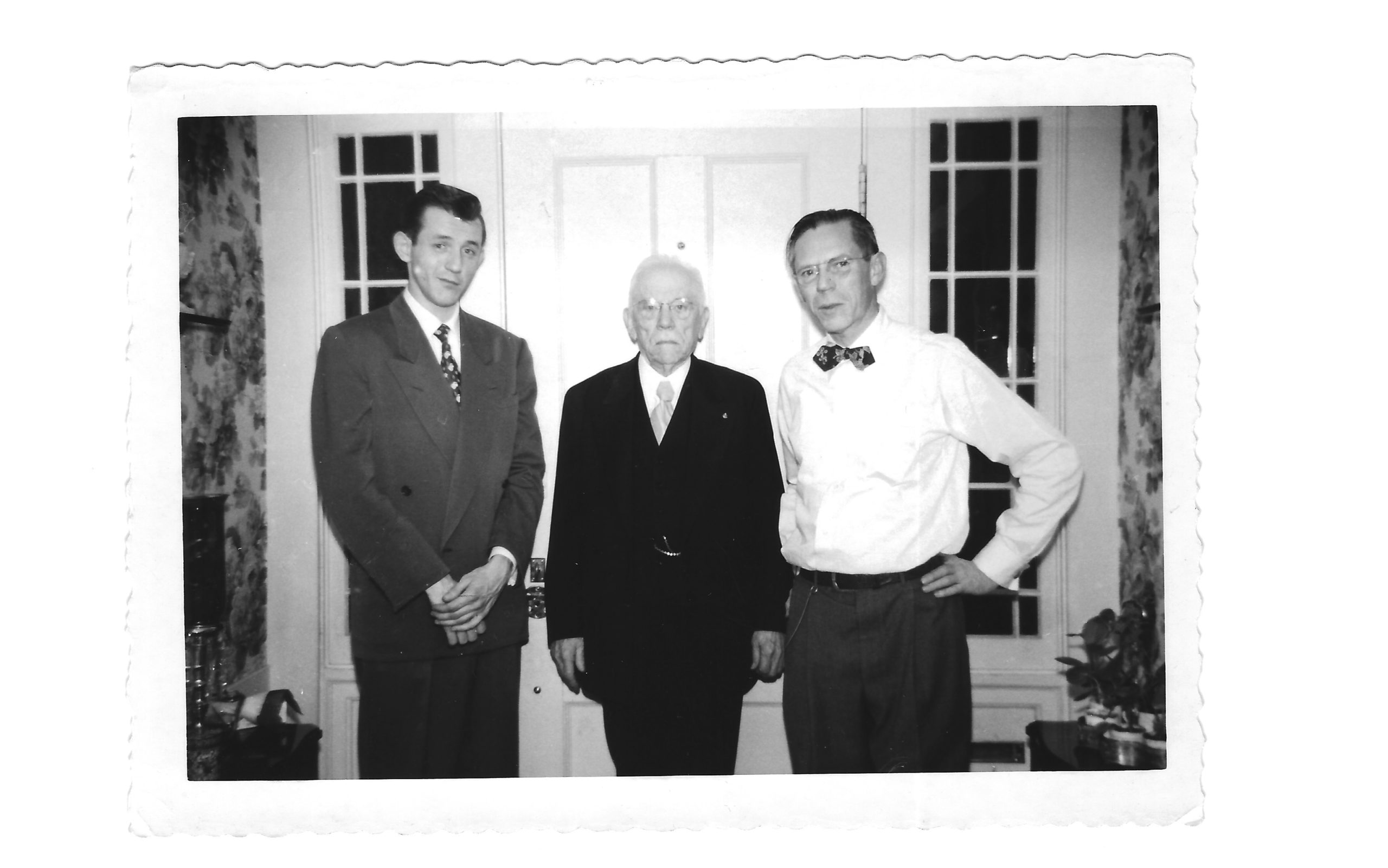

Three generations of O’Connell patriarchs are shown in this photo, taken in Chicago sometime in the 1950s. In the middle is Joseph John O’Connell I. At right is his son, Joseph John O’Connell II, and at the left is his son, Joseph John O’Connell III, who was an art teacher, artist-in-residence and widely admired sculptor at the College of St. Benedict in St. Joseph.

This house in Chicago, where Joseph John O’Connell I lived until his death in 1959, is now a historic landmark.