by Dennis Dalman

A steady loss of memory in a loved one can cause heartbreak and ever-creeping dread that leads to a mental-emotional struggle between stark despair and glimmering hope.

In Tracy Rittmueller’s new book of poetry, she vividly evokes that struggle, but like a verbal alchemist she wrings from that despair not only hope but renewed bonds of love.

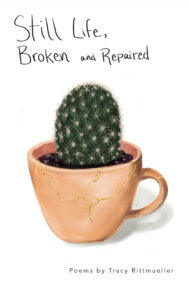

The book of 45 poems is entitled “Still Life, Broken and Repaired.” Its three sections echo the stages of the struggle against memory loss – from shadows to light, from grief to hope, from despair to transcendent love.

Rittmueller, a Sauk Rapids resident, is the founder of Lyricality, a central Minnesota organization that fosters the art of empathy through poetry and stories. Many of its members are writers and other artists who live in St. Joseph. Rittmueller is also a Benedictine oblate, a lay-member associate of the St. Benedict’s Monastery.

This year, she was awarded a Minnesota State Arts Board grant to develop workshops that engage adults living with dementia to become creative writers.

Rittmueller said the lyrical poems in “Still Life, Broken and Repaired” were inspired or informed by personal experiences.

I.

In the volume’s first poem, the woman/poet watches her husband sleep as she feels a fearful wariness buttressed by a tender solicitude. There is a hint the woman knows her husband has been diagnosed with dementia, but he does not know it yet. It’s entitled “Sonnet to Negotiate Peace with Your Dementia.”

“You’re dozing in your rocker, feet planted.

You clutch the chair’s arms, appearing prepared

for the shock of bad news, your neck slanted

head jutting forward. Oh my dear gray scared

bird, while invisible worms still burrow

you stop searching for a table to hold

your reading glasses. And then you furrow

your forehead, begin to snore. You turn old.

The unread want ads lie on your stomach.

They rise and fall between us as we breathe.

Will I tell you? No, I’d rather mimic

You now, observe in silence all that seethes.

I thought I might explain why we’re broken.

But sleep. This, too, will remain unspoken.”

II.

In the second section of the book, the poems practically erupt with soul-searching questions, along with mourning and grief, as the woman/poet, hounded by sorrow, tries again and again to reconcile the man’s fading, flickering memories with how to move into the future, together, with hope.

The following is the last stanza of “But Would I Still Desire to Plant?”

“Nothing prepared me for this, although

I might have recognized the truth

That late autumn evening later

that year, after our harvest of carrots –

how little time remained for us before

your mind would begin its slowdown.

Never did I think that one day

looking back I would ask myself,

would I still have desired to plant

with you, had I known our lives would

come to this unknowing?”

In “What Is There About Us Always,” the poet muses about a broken teacup given to her by her husband years before – a cup she’d accidentally broken. Her husband retrieved the cup’s shards and glued them back together. The images in the poem echo the front cover of the book, a mended teacup holding a cactus.

The following is the last third of that poem:

“Later

you brought home a miniature cactus

encircled with thorns. You potted

potentially maiming barbs, tamed them

in that teacup, fragile as the distinction between scars

and art. Sometimes I worried your tenuous

memory will fracture our companionship

But I know who you are, always the one

who salvaged those wrecked remnants –

my heart – to restore that broken vessel – me.”

III.

In the book’s third section, the wondrous beauties of nature practically bloom wildly on every page, interlaced with so many of the poems’ lines. There are oceans, sea gulls, a swarm of dragonflies, Japanese beetles, lilacs, bees, trees, purple clover . . . The vast profusion of all of the flora and fauna not only console the poet and her husband, but they also spell the way to a mended relationship, the rebirth of hope and the bonds of love that are renewed, strengthened through adversity.

In the last poem of the book, Rittmueller gives a poetic meditation about “kintsugi,” the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold mortar, which is a metaphor for humans embracing their imperfections. The poem is, again, an echo of the book’s cover – the mended teacup.

Dedications

“Still Life, Broken and Repaired” is receiving praise from readers/critics.

From Dennis Vogen, author of the graphic-novel series, “Brushfire.”

“(It) is a work that starts in the key of grief and plays – sometimes desperately, sometimes joyously – until it modulates into the sound of hope.”

From KateLynn Hibbard, author of “Simples.”

“Rittmueller strikes a delicate balance here, drawing strength and inspiration from nature and art, while leaving the reader with admiration for the couple’s abiding love.”

“Still Life, Broken and Repaired” is dedicated to Rittmueller’s husband, Kenneth Allen Karner Rittmueller.

In the “Acknowledgments” section of the book, Rittmueller wrote this: “His (Kenneth’s) love, support and zany playfulness help me to appreciate the daily moments of joy and serenity, even while we carry the increasing (and sometimes terrifying) losses that come with aging. Thank you, Bunky, for the beautiful, astonishing light of your being. I love you to infinity and beyond.”

Published by Lyricality Press, “Still Life, Broken and Repaired,” is available via Amazon.com or at IngramSpark: bookshop.org/shop/ingramsparkbooks.

Poet Tracy Rittmueller and her husband, Kenneth, enjoy a visit to Clemens Gardens in East St. Cloud. The couple has always loved nature as a fulfilling part of their living their lives together.

This is the cover of Tracy Rittmueller’s new book of poetry. The cracked, mended teacup with cactus is evoked in two of the book’s poems, a metaphor that relationships that are stressed, broken and difficult can be mended, made to work and then lead to a strengthened bond of love.